Death Valley, California, is a place of extremes. The brutal summer sun and intense heat of the Mojave Desert bake most of the vivid color from the landscape. In bright sunlight the dull tans contrast with the bright blue sky. After sunset, and before dark, the dull tans become duller grays, a situation perfect for even duller photographs.

One of the contrasts in the 156-mile-long depression that sits between the Amargosa Mountain Range on the east and the Panamint Mountain Range on the west is that water actually exists in Death Valley. Badwater is 282 feet below sea level and it is the lowest place in the Western Hemisphere.

Badwater Basin at Dusk | ©2011 David Allio

So, how is it possible to create excitement from dull and color from gray?

One solution is to borrow a technique from the school of film photography and the era of screw-in color compensating filters. Underexpose by between one-third and two-thirds of an f/stop to increase whatever color saturation is available. Then use a filter to add color – in this case blue to represent the water.

Just because the in-camera electronics say so does not always mean it is the correct or most creative way to present a scene. Usually the in-camera information is an average or sometimes a biased average of the information provided to the evaluation systems. My goal is not to make average pictures. I want my photographs to stand out from the average. And in this era of immediate results and intense deadline pressures, if a photograph does not come out of my camera the way I want it presented, there rarely is an opportunity to correct or enhance the image later – hence the mantra: “Do it right, right now.

This is the original color digital version of this photograph of Badwater Basin in Death Valley. It was created using Nikon D3 camera equipped with an AF-S Nikkor 24-70mm 1:2.8G ED lens. With the focal length set at 24mm the exposure settings were an aperture of f/5.6, shutter speed of 1/160th second, and film speed 400 ISO. The actual exposure for this after-sunset photograph was two-thirds of a stop under what was recommended by the in-camera meter. The white balance in the camera was set for about 5000K less that the actual ambient light.

Rhyolite, Nevada

There is a difference between a photojournalistic and an artistic interpretation of a scene. Basically, a photojournalist is bound to the accuracy of a scene as presented through the camera, lens, and exposure. After a photograph is created by the photojournalist, further interpretation is conducted by a photo editor, art director, or publisher.

By contrast, an art photographer is likely responsible for the creation of the original image as well as presentation of the finished image. Therefore, creative, artistic interpretation is virtually unlimited in post-production.

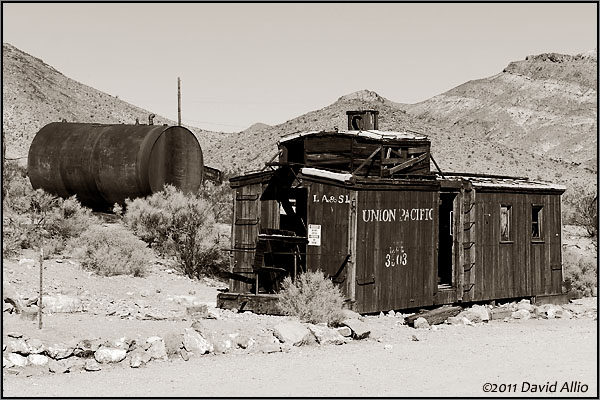

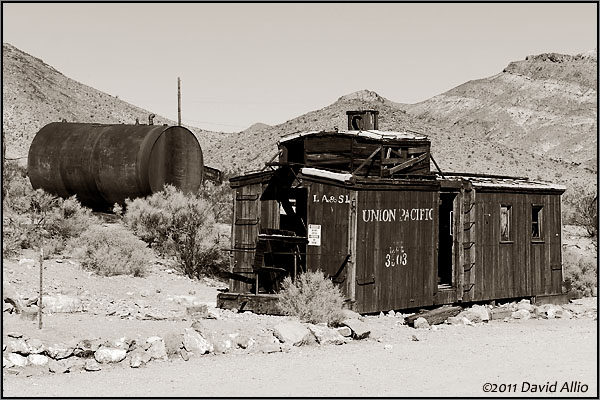

End of the Line | ©2011 David Allio

My response in this case is simple: My creative choice was the same as a painter. Just because the original was created as a photograph, complete with a normal spectrum of colors, does not mean that my artistic representation of the scene as an art print should be limited to a photojournalistic presentation of the scene. Confidentially, I selected a palette of rusted reds and browns because the vivid blue sky of the original color photo just did not represent the decomposition and decay of the scene.

The original color digital version of this photograph was created using Nikon D3 camera equipped with an AF-S Nikkor 24-70mm 1:2.8G ED lens. With the focal length set at 70mm and exposure mode of Manual, the exposure settings were an aperture of f/13, shutter speed of 1/800th second, and film speed 400 ISO. Lighting was bright early afternoon sunlight. Colorization was achieved in post production.

When the term “Wild Horses” Equus ferus is mentioned, the common visual involves running herds of wild mustang. But there are other, colorful pastoral scenes, of wild horses and burros grazing in and near the harsh Mojave Desert.

Although cautious of people in their territory, these nearly half-ton creatures have been known to frequently approach visitors. These horses colored as pintos, blacks, cremellos, palominos, bays, browns, and sorrels may appear calm, docile, and even tame as they forage for food. But, they are still animals inhabiting a wild and extreme environment.

Wild Horses of Cold Creek | ©2011 David Allio

The wild horses and burros of Cold Creek have a lineage that can be traced back to regional ranching and settlement days. Most wild horses resemble Draft horses, Quarterhorses, Morgans, Thoroughbreds, and Standardbreds.

Two US government agencies oversee the management of this land and the inhabitants. These are the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the Forest Service (USFS). Based on their statistics, the area designated as the Spring Mountain Wild Horse Territory and the Wheeler Pass Herd Management Area is approximately 273,000 acres and, as of 2011, has about 273-328 wild horses and 101-152 wild burros.

Not everything in the desert is edible, let alone nutritious, or colorful. But in that desert area, there are five main plants – desert needlesgrass, indian ricegrass, big galleta, winterfat, and white bursage – supporting the wild horse population. These food sources are impacted by weather and wildfires. Water is also a concern. Food sources and water are not always close to the other. As a result, herds are constantly moving across the desert.

Despite hardships, both government officials and local observers agree that the herds of wild horses in this area are growing. Yet, they tend to disagree on the best ways to manage and interact with these nomadic animals.

Professional wildlife photographers have been known to return to the same locations for years, researching their subjects, habitat, and environment. They study and wait, preparing with the proper camera and lens combinations for timing to present an idyllic scene. Dedication to meticulous research leads to opportunities for an incredible, sometimes once-in-a-lifetime, image.

Photojournalists rarely have that luxury as they document scenes constantly subjected to compelling time constraints and relentless deadlines. They have to be quick studies, evaluating the safety of their surroundings before the production process even begins. Then quick, experienced decisions influence composition and accuracy in site representation.

For this illustration, my first experience with wild horses, the photographic production considerations included: camera and lens selection, followed by depth of field considerations – depth of field because of the distance involved between the camera, subject and background. Depth of field determines the f/stop range. The f/stop then dominates the exposure formula for film speed and shutter speed. For this image, a 200mm lens was selected. The other Manual Mode settings were: f/10 with a shutter speed of 1/1250th of a second using an ISO setting of 200.

Thank you to Krystal Johnson, the Wild Horse and Burro Specialist of the Southern Nevada District/Pahrump Field Office of the United States Bureau of Land Management, for providing the research information contained in this narrative.

You must be logged in to post a comment.